Rescuing a decade old scientfic database

Intro

How do you know you’re old in tech? The tell-tale sign is that your new projects and up being about saving your old projects. How old? Like DECADES old. But I’m getting ahead of myself here… let’s introduce our characters.

How did we get here?

When I was a wee little lad, my first encounter with programming was as a biochemistry student, staying over the summer at Oxford. Funded by Wellcome Trust, that summer thrust me into the tech trajectory that I stayed on for over 10 years now. What was the mission? Researchers typically stored the parameter files on random FTP servers or shared them via email. Our task was to build a database of lipid parameters for molecular dynamics simulation.

Having no prior coding experience, what could you expect from a student? The product was a database called Lipidbook, a simple CMS-like app for researchers to upload these parameters and link them to their papers (for proper citation by their peer) . The summer ended, a paper got written up and that’s it. End of story, right? That’s the reality it in terms of science sustainability for software development: there often is funding to develop new tools but once it’s out there… the funding situations becomes more “dire”.

The troubles begin

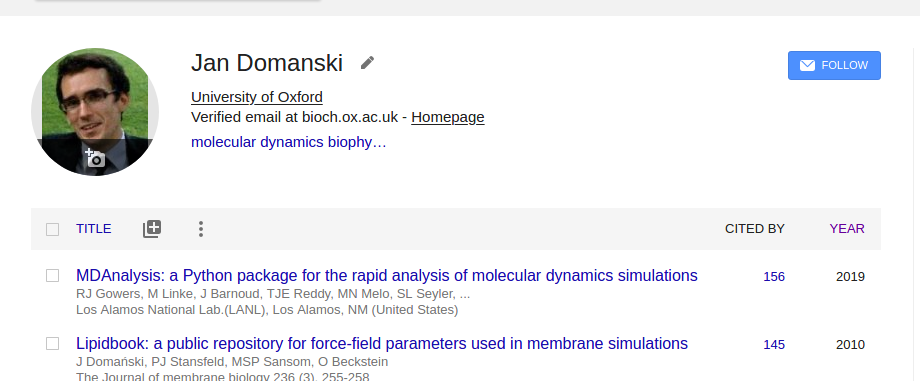

With the Lipidbook published the researcher started to publish stuff to it. Not like millions of files but enough to make the tool valuable to the community. People not only started depositing but also citing the paper. So far it’s my 2nd most cited paper of all time: a software tool paper that overshadowed other “actual” science papers.

Remarkably, the system held with little human intervention. For nearly a decade the website run of a mac mini in a cupboard in Oxford. Yeah, sometimes it needed a reboot but beyond that, smooth sailing! Everything was kind of “MVP” (minimal viable product) with bash scripts and cron jobs running support functions. The real crisis began when the people running the hardware moved out of the lab. Without anybody to occasionally press the reset button, or without any SSH access, we were stranded. The website was down for days, then weeks then months. People kept messaging us but we simply didn’t have the time.

How can we fix this?

The impetus came from Phil Stansfeld and Oliver Beckstein, both mentors of mine, who equally facilitated “good decisions” and suppressed “questionable choices”. What should we do to get this service up and running without a tremendous amount of work? Where should we host it? Typically, academia prefers to host things in-house, rather than on AWS. Why is that strange choice, you might ask? Comes down to the funding model: once you get your grant money in science, you can buy a lot of hardware, but running that hardware will largely be done by the university. Even with your grant money running low, you don’t have to cut down on usage. It’s really unfortunate that funding bodies haven’t changed their model to include year-long support costs. That wouldn’t be the case with AWS, billed per hour, as you can imagine. Despite that, Oliver wanted to push ahead with AWS. This project is an interesting example of using AWS in a cost-efficient way for science infrastructure. But how do we yank Lipidbook from a single MacMini to the cloud? Enter Pulumi and AWS.

AWS needs no introduction, it’s the mother-of-clouds, the Amazon Web Services. Pulumi is tool that allows you to manipulate and manage AWS resources via declarative programs that specify the desired end-state of your infrastructure.

Assembling a web app

Will this be a primer on Pulumi or AWS? Probably not but what I’ll attempt to do here is to outline how these pieces fit together. What’s the first thing that comes to mind? We’ll probably need an EC2 instance on AWS to host the webserver and all. But let’s take a step back and start by putting together our networking layer, and the boilerplate on which the app will stand.

BEWARE

All examples given here will be in Typescript, the programming language that is the love child of the web in 2020. Pulumi comes with a variety of other SDKs, including Python, so you’re free to choose between them.

Networking layer

import * as awsx from "@pulumi/awsx";

const vpc = new awsx.ec2.Vpc("custom", {

numberOfAvailabilityZones: 1,

});

This will create our VPC with public and private subnets. VPC will ensure the isolation of all the services inside. Single availabilility zone to keep the costs super-duper low.

Backup bucket

What’s the next useful thing to add? The Lipidbook database needs to be backed up regularly, so let’s create an S3 bucket to hold the backups

import * as aws from "@pulumi/aws";

const backupBucket = new aws.s3.Bucket("backup-bucket", {

bucket: config.backupBucket,

serverSideEncryptionConfiguration: {

rule: {

applyServerSideEncryptionByDefault: {

sseAlgorithm: 'AES256',

},

},

},

});

Notice that the bucket contents get encrypted, because why not!

SecurityGroups

The EC2 instance needs to know on which ports to accept the connections, we probably want to keep 443 and 80 ports open. To define that behavior, we create a SecurityGroup

const securityGroup = new aws.ec2.SecurityGroup(

"security-group",

createSecurityGroupArgs(config)

);

The createSecurityGroupArgs is a helper function to create the SecurityGroup configuration that you need. The details are left to the eager reader!

KeyPair access

Next, we’ll need a KeyPair to access our EC2 instance via SSH and do servicing/maintenance on it.

$ ssh-keygen -t rsa -f rsa

We then import the publicKey part

const keyPair = new aws.ec2.KeyPair(

"key-pair", {

keyName: `lipidbook-${config.environmentName}`,

publicKey: config.publicKey,

});

Amazon Machine Image

Lastly, we need to get an amazon machine image for our Ubuntu version up and running

const size = "t1.micro";

const ami = aws.getAmi({

filters: [{

name: "name",

values: ["ubuntu/images/hvm-ssd/ubuntu-trusty-****"],

}],

owners: ["099720109477"], # canonical

});

Getting the webserver

All the pieces are assembled now: we have the VPC for networking, we have a security group and the machine image. Let’s get the final piece assembled!

const server = new aws.ec2.Instance("webserver-www",

createEC2Args(config, vpc, size, securityGroup, ami),

);

Now obviously this is just a blank EC2 box. It still needs to be provisioned to run our app. This is beyond the scope of this post but we’ve used Hashicorps Vagrant for that.

Elastic IP

The EC2 instance we’ve created does have a public IP but it keeps changing between each machine spin-up. To get our DNS setting working we’ll need an elastic IP.

const elasticIp = new aws.ec2.Eip(

"elastic-ip",

{

instance: server.id,

}

);

No matter what the instance public IP is, this ElasticIP will not change and can be used to configure the DNS.

DNS Configuration

This is the last piece. Again, I’m omitting the details of createARecordArgs and createCNAMERecordArgs.

There are obviously important details… But let’s allow the big picture to take priority.

const record = new aws.route53.Record(

"record",

createARecordArgs(config.targetDomain, elasticIp),

);

const aliasRecord = new aws.route53.Record(

"alias-record",

createCNAMERecordArgs(config.targetDomain, config.aliasDomain),

);

Future work

There is a number of things here that I’m not happy about and could be improved:

-

With the app we’re running, given it’s age, I see no incremental migration path. It’s a re-write and these don’t get funded.

-

The EC2 instance should ideally be in a private subnet, all HTTP requests should go via a LoadBalancer, and direct access should be possible only via SSH hopping over a bastion box.

-

The database is hosted directly on the EC2 instance, ideally, it should run on its own RDS instance. So that when the EC2 goes down the database is not lost.

Closing

Amazon Web Services model has not been super popular in academia. The reasons are probably related to funding structure and grants. However, for running scientific infrastructure that often needs to be maintained for years, it is a suitable choice. The entire cost for us to run this operation is 35$ / month, aka peanuts. Using tools such a pulumi, the infrastructure can be quickly spun-up and modified. The pulumi program presented here was written in typescript but SDKs for most popular languages exist (including Python). The scientific community could run many more pieces of infrastructure for less, in a more maintainable fashion using cloud providers and declarative infrastructure.